History of the IRCA

Road construction is storied in Iceland, since transport has always been extremely important for the country’s population and urban development.

Iceland’s first engineer was hired more than 130 years ago, in 1893, into a position which later became Chief Civil Engineer. In 1918, this position was divided into two separate offices — Director of Roads, and Director of Lighthouses.

From these two offices the Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration developed as an institution.

The Chief Civil Engineer

The first Chief Civil Engineer was Sigurður Thoroddsen, the first Icelander to complete an education in engineering. Sigurður held the position until 1904, when he accepted a teaching position at Lærði skólinn, the institution that would go on to become Reykjavík College. Two others would go on to hold the position of Chief Civil Engineer: Jón Þorláksson and Thorvald Krabbe.

The office would eventually be divided into the Director of Roads (Geir G. Zoega) and the Director of Lighthouses (Thorvald Krabbe.) Out from these two offices the Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration (IRCA) would be developed.

Construction in the first years

Focus was placed on modest projects initially. In 1894 the construction of roads for use by loaded carriages over the summer was discussed. Paths heading east out from Reykjavík, Rangárvallasýsla and towards Geysir were deemed important. The rural, land-locked sections of Árnessýsla, Eyrarbakki and Borgarfjörður followed, with areas around Blönduós, Sauðarkrókur, Akureyri, Húsavík, Búðareyri in Reyðarfjörður, and Fagridalur developed soon after. Later on road construction began across Iceland’s various heaths: Mosfellheiði, Hellisheiði, Holtavörðuheiði, Grímstunguheiði and Hrútafjarðarháls, to mention a few.

As is the case now, many projects were on the docket in those days. Bridges across the rivers Ölfusá (1891,) Þjórsá (1895,) and Blanda (1897) were constructed. All three bridges were designed and constructed abroad. When the bridge over Ytri-Rangá (1912) was built it became the first bridge to be fully constructed in Iceland.

At this point in history the automobile arrived, followed by an increase in road use. This increase has since continued with no end in sight. In response, the IRCA began to add to its arsenal of equipment, purchasing in 1920 four vehicles for gravel transport, followed by a road compactor and heavy machinery for gravel making. During the second world war, larger industrial machinery saw use in Icelandic road construction.

The development of the road system

The Icelandic road system has grown extensively since the beginning of the 20th Century. In 1917, the road system measured around 500 km. Eight years later, there were 612 km of roadways and 712 km of carriage roads. Following World War II, in 1946, the system totalled in at 4,400 km of roads. During this period of development, the focus was not only placed on lengthening the road system and building more bridges, but also on strengthening and elevating the existing road system so that it could be utilized in Icelandic winter conditions.

Work on modernization of the road system continued past 1970. A large milestone was reached when the ring road was completed, following the addition of bridges over Skeiðarárssandur in 1974. Ultimately it can be said that, upon reaching that milestone, the road system was broadly, for all intents and purposes, finalized, with only qualitative improvements to be made.

The projects still kept coming. During the 1970s, emphasis was placed on paving the pre-existing gravel roads present in the system. Around 1980, large initiatives were undertaken in pursuit of this, with some years seeing more than 300km of gravel roads being transformed into paved ones. The coating used was a good solution for less travelled Icelandic roads. It adequately serviced the present traffic and, since it was much cheaper than asphalt, resulted in a greater amount of hard-surface roads, than if asphalt had been used. Single-lane coating was even utilized to cover more kilometres. Icelanders desired to be rid of potholes and dust.

In 1994, 2,840 km of highways had been coated. These days, a little less than 6,000 of the country’s 13,000 km of highways are coated. Despite the large percentage of gravel roads, 97% of all traffic is on coated roads, and increasingly on asphalted roads. Currently, emphasis is placed on increased asphalt paving, reducing coating in order to meet the needs of constantly increasing traffic.

Challenges of our times

The biggest challenges for contemporary Icelandic road construction are centered on the widening of roads, and subsequent separation of traffic directions, thereby increasing traffic safety. Furthermore, there are multiple large projects concerning the renovation of bridges waiting to be undertaken.

Increased tourism in Iceland has completely changed the Icelandic environment, since many of the three million tourists that travel to Iceland each year choose to travel on their own by renting a car. This poses a great deal of challenges for the IRCA, both pertaining to its mission of improving the road system, as well as providing services for both tourists and the Icelandic public. There is a steadily increasing demand for improved winter service, due to the ever-growing quantity of winter tourists. This also calls for effective communicating of information in more languages than Icelandic.

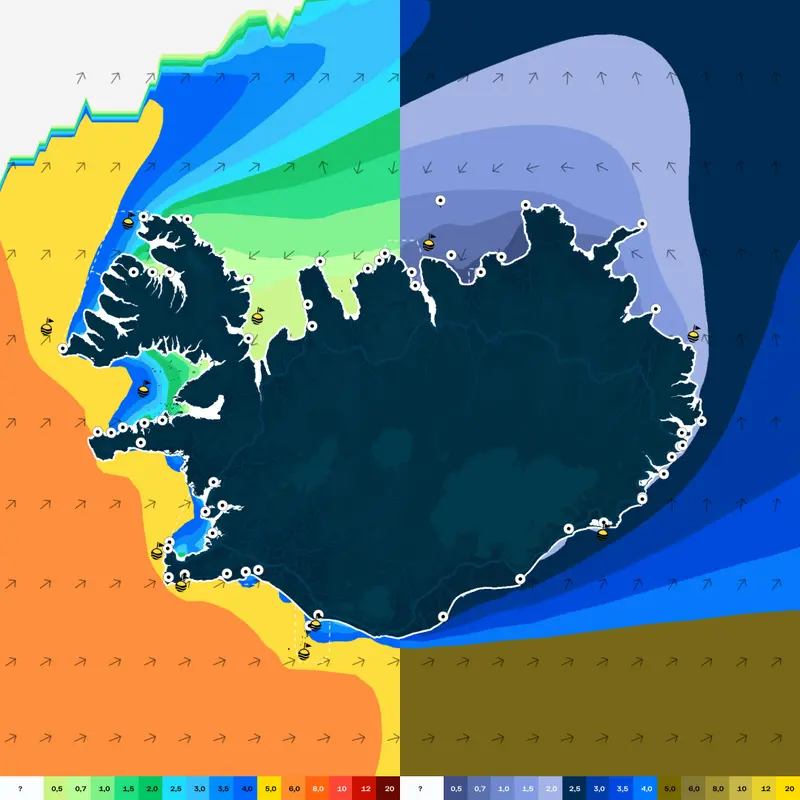

Information on driving and road conditions present on umferdin.is is currently available in three languages: English, Polish, and Icelandic. This is one facet of IRCA operations which shows the change occurring within the institution, and the shifting of its priorities. The IRCA’s projects are also increasingly varied in comparison, with road system service, services for travellers, the operation of tunnels, and administration of land, sea and air-based public transport all falling under the IRCA’s umbrella. The IRCA also consults on the design of port structures, maintains sea defences, operates Landeyjahöfn, maintains and services 103 lighthouses, and monitors ocean currents. Seafarers can obtain information from the IRCA’s website sjolag.is. Multifaceted research is furthermore conducted by the institution, concerning road construction, port construction, or other ocean-related research.

The importance of transport to modern society is unmatched, as it can not prosper without the presence of accessible transport, and transport structures, all year round. This becomes crystal clear when closures occur on traffic-heavy roads. It should be kept in mind that the road system is the most expensive property the nation possesses, and so it needs to be maintained for the benefit of all.

Historical overview

- 1894 The construction of drivable paths for transport first mentioned in Icelandic law.

- 1912 The first steel bridge completely made in Iceland built across Ytri-Rangá river.

- 1917 The road system estimated to be around 500km

- 1918 The office of the Chief Civil Engineer becomes two separate positions; Director of Roads and Director of Lighthouses.

- 1926 The IRCA acquires its first road grader

- 1930 The road system around 1,500km

- 1946 Drivable roads around 4,400km

- 1970~ The start of the project of building paved roads all around the country

- 1974 Opening of the ring road

- 1994 Paved highways in Iceland reach 2,840km. Registered vehicles in Iceland around 132,000*

- 2018 Paved roads in Iceland around 5,700km out of 13,000km. Registered vehicles in Iceland around 311,000*

- 2019 The ring road fully paved

- 2023 There were approximately 140 single-lane bridges on the Ring Road in 1990. With the opening of bridges across Núpsvötn and Hverfisfljót in 2023 they are now down to 29.

The Icelandic Road Museum

The IRCA operates the Icelandic Road Museum, Vegminjasafnið.

The Icelandic Road Museum’s history spans a few decades. Various items and information from earlier times have been gathered, and older machinery used for road construction has been renovated for preservation. The museum’s beginning can be traced back to the IRCA’s employee association collecting old road building memorabilia. The IRCA officially took over the management of the museum in early 1989.

The museum owns a considerable number of historical artefacts, tools, and equipment. Included in the collection are machines used for road construction, worksheds, tents, photographs, measuring equipment, office items, traffic signs, building tools, saddlery, models and much more.

For the Icelandic Road Museum, the whole country is its venue. Naturally, some relics for preservation — for example, old roads and bridges — are of the type that cannot be displayed in buildings.

In 2002, the Technical Museum in Skógar entered into an agreement with the IRCA to exhibit the Icelandic Transport Museum’s pieces. The Technical Museum is now a part of the Skógar Regional Museum.

The Icelandic Road Museum occupies one section of the Technical Museum, wherein various pieces are showcased, such as front loaders, road graders, a steam roller, a snow truck, a work tent with related equipment, and much more.

Further details on the Icelandic Road Museum can be found in the article on The Icelandic Road Museum from 2007 (only available in Icelandic.)